Note on Principle 2 of Principled Negotiation: Focus on Interests, not Positions by Legum

Principle 2 of Principled Negotiation: Focus on Interests, not Positions

Introduction:

One of the principles or strategies of principled negotiation is focusing on interests and not positions. This note will discuss the meaning of positions, the meaning of interests, why there should be a focus on interests and not positions, and how interests are identified.

Meaning of Positions:

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a position is “a point of view adopted and held to.” Similarly, the Cambridge dictionary defines a position as “a way of thinking about a particular matter; opinion.” In light of these, “Free SHS is the best thing to happen to Ghana since independence” is a position. Also, “A 24-hour economy is better than free SHS” is also a position.

Often, in a dispute or a transaction, positions appear to inconsistent or incompatible. In a dispute, for instance, one person says, “Only NPP can transform Ghana,” and another person says, “Only NDC can transform Ghana.” In a transaction, a customer may say, “This product is only worth Ghc 100,” and the seller may say, “The product is worth Ghc 200.” These are all inconsistent positions.

Meaning of Interests:

Interests are a person’s needs, desires, interests, hopes, aspirations, fears, and concerns. According to Fisher and Ury [1],

Interests motivate people; they are the silent movers behind the hubbub of positions. Your position is something you have decided upon. Your interests are what caused you to so decide.

Summarily, the interests underlie the positions. Put differently, the positions are smokescreens for the interests. Thus, while the statement “Free SHS is the best thing to happen to Ghana since independence” is a position, the bundle of desires and concerns that cause a person to adopt this position are his interests.

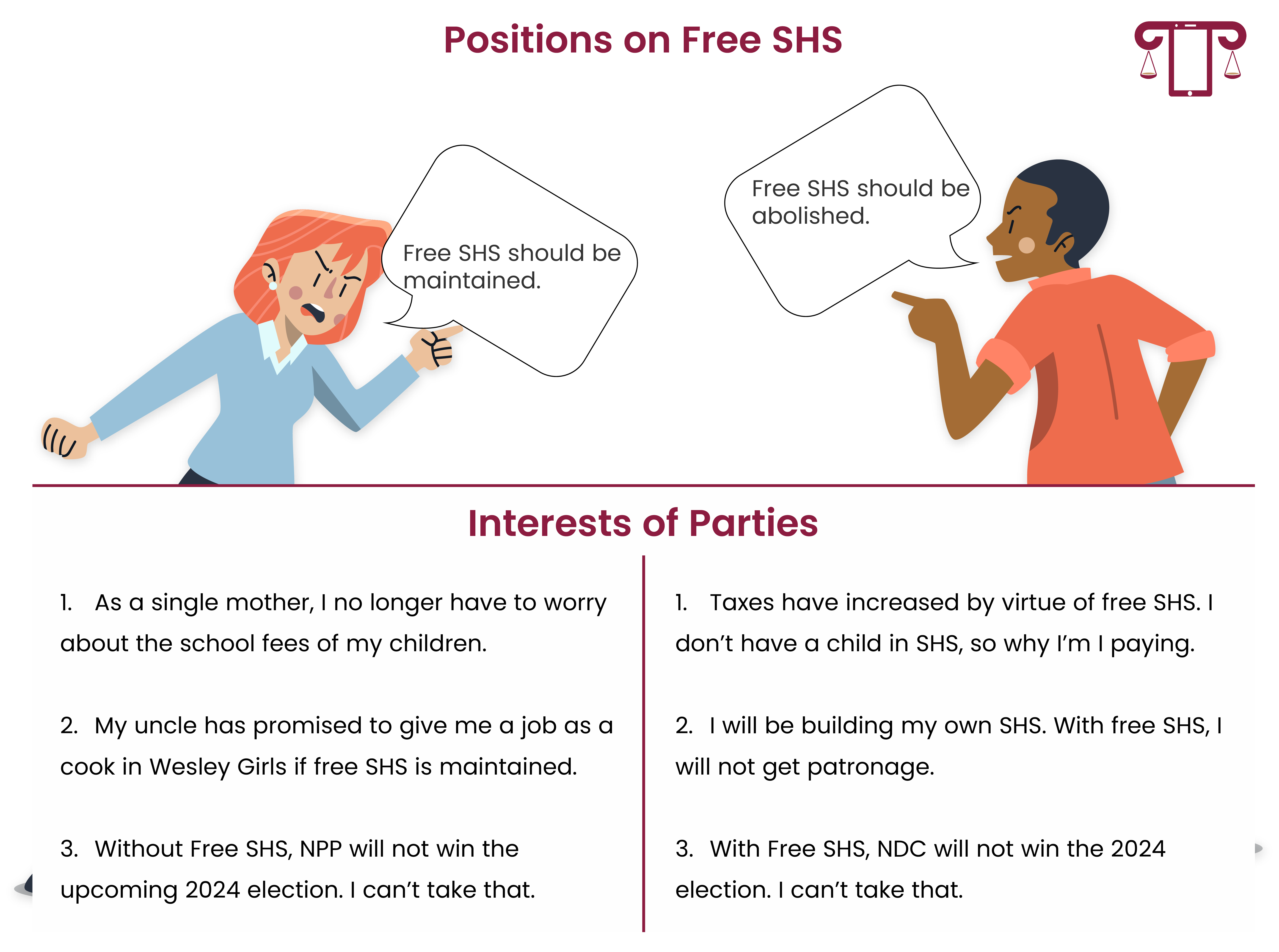

The following illustration is useful:

From the illustration above, the interests of the disputing parties are the reasons they take their respective positions. While they make their positions explicit, they are less likely to make their interests explicit. Nonetheless, the interests underlie the positions.

Why the Focus should be on Interests and not Positions:

Given that interests underlie positions, and positions often appear to conflict, it may be said that the interests of the parties are actually what give rise to a dispute. Put differently, the interests define the problem: This is because, based on the interests, a person adopts a position, which may be contrary to the position adopted by another person based on his own interests.

With the above understanding, there should be a focus on interests and not positions for two reasons:

1. Several Positions can Satisfy the Same Interests:

The same set of fears, hopes, desires, concerns, among others, which constitutes a person’s interests, can give rise to several positions. For instance, a person desirous of a successful life can adopt the position that he wants to be a lawyer, doctor, or politician. Similarly, a person fearful that her children would not pursue secondary education may either adopt the position that secondary education should be made free or adopt the position that government should create jobs so she can be gainfully employed and provide for the educational needs of her children.

By focusing on interests, a party can easily adopt a position that still satisfies his interests yet is not inconsistent with the position of another party. Fisher and Ury [1] gave the following succinct illustration of how Egypt and Israel resolved a dispute by adopting different positions that still satisfied their interests:

The Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty blocked out at Camp David in 1978 demonstrates the usefulness of looking behind positions. Israel had occupied the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula since the Six Day War of 1967. When Egypt and Israel sat down together in 1978 to negotiate a peace, their positions were incompatible. Israel insisted on keeping some of the Sinai. Egypt, on the other hand, insisted that every inch of the Sinai be returned to Egyptian sovereignty. Time and again, people drew maps showing possible boundary lines that would divide the Sinai between Egypt and Israel. Compromising in this way was wholly unacceptable to Egypt. To go back to the situation as it was in 1967 was equally unacceptable to Israel.

Looking to their interests instead of their positions made it possible to develop a solution. Israel’s interest lay in security; they did not want Egyptian tanks poised on their border ready to roll across at any time. Egypt’s interest lay in sovereignty; the Sinai had been part of Egypt since the time of the Pharaohs . After centuries of domination by Greeks, Romans, Turks, French, and British, Egypt had only recently regained full sovereignty and was not about to cede territory to another foreign conqueror.

At Camp David, President Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Begin of Israel agreed to a plan that would return the Sinai to complete Egyptian sovereignty and, by demilitarizing large areas, would still assure Israeli security. The Egyptian flag would fly everywhere, but Egyptian tanks would be nowhere near Israel.

Consider another illustration where two siblings are in disagreement over who should keep the orange aunt Theodora gifted. Sibling X says he should keep the orange as the older sibling. Sibling Y says she should keep the orange as the younger sibling. The positions on who to keep the orange are incompatible. However, if Sibling X is asked why he wants to keep the orange, he may reveal that he needs the seeds for an experiment and is not really interested in the orange juice. With this revelation, it is possible for Sibling Y to agree that she will carefully squeeze out the juice and leave the seeds in a good state for big brother. With this proposition, Sibling X may then change his position from wanting the entire orange to wanting the seeds of the orange in a good state.

Summarily, if positions appear incompatible, there would be no real way of resolving those positions unless the interests that underlie the positions are known. Once those interests are known, the parties can work to find compatible positions that still ensure the satisfaction of their interests.

2. Behind Opposing Positions are Shared and Compatible Interests and Conflicting Interests:

When the focus is on positions, it is often position X against position Y. The parties, by virtue of having incompatible positions, see themselves as being less likely to agree. However, behind the incompatible positions are some compatible interests that can serve as building blocks for the parties to reach an agreement.

To illustrate, consider the following disagreement between two students in Group B of the Greenhill Campus of the Ghana School of Law:

- John Zigah: I sit at the back, which is warm, so the AC needs to be at a lower temperature.

- Clara Baaba Barnes: I sit close to the AC, and I feel cold when the AC is at a lower temperature.

At first glance, these positions appear incompatible. John’s preference for cooler temperatures clashes with Clara’s preference for warmth. However, examining the interests behind their positions reveals both shared and conflicting goals:

Shared Interests (Compatible):

- Both students want a comfortable environment conducive to learning.

- Both students value their ability to concentrate during lectures without physical discomfort.

Conflicting Interests:

- John seeks a cooler environment because the back of the classroom is warm.

- Clara seeks a warmer environment because sitting near the AC makes her uncomfortably cold.

Given that there are some shared interests in creating a productive and conducive learning environment, the parties may reach an agreement by:

- Adjusting their sitting positions: John could move closer to the AC, and Clara could move further from it. They are more likely to do this because they are collectively interested in creating a conducive learning environment.

- Making personal provisions: John could bring a portable fan, and Clara could use a light sweater or scarf to stay warm.

The above two agreements are only possible because the shared commitment to creating a conducive learning environment was used as a building block for the parties to make adjustments and reach an agreement.

How to Identify Interests:

Often, parties to a dispute or transaction often state their positions and not the interests that underlie those positions. In a dispute on whether free SHS should be maintained, a party who would be contracted as a supplier under free SHS, while voicing out his position that it should be maintained, is unlikely to reveal his fear that he will not get the contract if the initiative is not maintained. Similarly, in a transaction, a seller who adopts the position that the buyer should pay more for his goods is unlikely to reveal that the excess profits he seeks will be used to purchase the latest iPhone for “babe.”

Given that people are less likely to reveal their interests, how then do we identify interests? Interests may be identified using the following:

- Using the basic human needs.

- Talking about the interests.

- Asking why the other party has adopted a particular position.

These are now explained.

1. Identifying Interests Using Basic Needs:

Every human being has several requirements for his survival and well-being. These requirements are referred to as basic needs, and according to Abraham Maslow, they include:

- Physiological needs such as food, shelter, and clothing.

- Safety needs such as personal security, stability, and freedom from fear.

- Social needs such as friendship, intimacy, acceptance, and a sense of belonging.

- Esteem such as self-esteem, status, recognition, and respect.

- Self-actualisation, which includes the need to achieve one’s full potential.

Collectively, these needs represent a person’s interests. Thus, almost every person is interested in getting food, shelter, security, being accepted, among others.

In the context of negotiation and the identification of interests, you may identify a person’s interests by averting your mind to the basic needs they have fulfiled and those they are yet to fulfil. For instance, a person who has fully made provision for his physiological needs or who is aware that those needs can be fulfiled with the resources at his disposal is less likely to adopt a position based on the desire to fulfil his physiological needs; he is more likely to adopt the position to enable him to fulfil some other unfulfiled need. For example, a person who has the capacity to fulfil his physiological need may adopt a position to fulfil his need for self-esteem, status, recognition, and respect. For instance, he may adopt the position that anyone who makes above Ghc 10,000, like him, should contribute towards the sustenance of free SHS. This position is underpinned by an interest in being respected for showing a commitment to help the less privileged.

2. Identifying Interests by Talking about the Interests:

Another effective way of identifying interests is through open communication, where all parties explicitly share their underlying interests with one another. This direct approach fosters transparency, minimises assumptions, and allows for a clearer understanding of each party's needs and concerns.

Various suggestions have been provided on how parties to a dispute or transaction can discuss their interests. These are:

- Make your interests come alive: Here, you are enjoined to be specific about your interests and adequately convey them to the other side . By being specific, you are required to provide concrete details about your interests.

- Acknowledge the interests of the other party as part of the problem: Here, you are enjoined to acknowledge and recognise that the other party has interests, just like you. The essence of acknowledging the interests of the other party is that by doing so, they are more likely to also listen to and appreciate your interests; the acknowledgement of interests then becomes reciprocal.

- Give your interests first before your position: Here, you are enjoined to present the interests that underlie your position to the other party before presenting your position. This way, your position appears to have a justification. If you were to present the position before the interest, the other party who objects to your position may not be listening when you are presenting the interests that underlie your position. The idea of presenting your interest first before presenting your position has been characterised in the course manual as “Put the problem before your answer.”

- Be hard on the problem, soft on the people: When discussing interests, apply all the responses to the people problem. For instance, when discussing interests, do not respond to emotional outbursts from the other party; put yourself in the other person’s shoes, listen actively, and acknowledge what is being said, among others. Also, you can forcefully discuss your interests, but in a manner that does not appear as an attack on the other party.

- Be concrete but flexible: As earlier highlighted, several positions can satisfy the same interests. In discussing your interests, be concrete in seeing to it that the interests are fulfiled, but also be open to fresh suggestions on how to fulfil those interests.

3. Asking why the Other Party has Adopted a Particular Position:

Another way of identifying interests is to ask yourself why the other party has adopted his position. When a party adopts a position, sometimes asking yourself why they have adopted that position can reveal a host of interests that underlie the position. Asking why triggers a cognitive process that causes you to think about and analyse their interests.

Conclusion:

In this note, we emphasised that in negotiating, it is essential to focus on the interests of the parties and not on their positions. This is essential for two main reasons. The first is that the same interest can give rise to multiple positions, some of which may be compatible with our own position. The second is that behind conflicting positions are interests that may be compatible. These interests can be used as building blocks to develop an agreement between the parties. We also discussed how to identify interests by discussing them, using the basic human needs, and by asking ourselves why the other party has adopted a particular position.

Users also Visited

More Alternative Dispute Resolution Notes, Cases with Briefs, and ResourcesAll LLB CoursesSpeed

1x